Millions of Americans have taken antidepressants for many years. What happens when it’s time to stop?

The New Yorker

By Rachel Aviv

April 1, 2019

Laura Delano recognized that she was “excellent at everything, but it didn’t mean anything,” her doctor wrote. She grew up in Greenwich, Connecticut, one of the wealthiest communities in the country. Her father is related to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and her mother was introduced to society at a débutante ball at the Waldorf-Astoria. In eighth grade, in 1996, Laura was the class president—she ran on a platform of planting daffodils on the school’s grounds—and among the best squash players in the country. She was one of those rare proportional adolescents with a thriving social life. But she doubted whether she had a “real self underneath.”

The oldest of three sisters, Laura felt as if she were living two separate lives, one onstage and the other in the audience, reacting to an exhausting performance. She snapped at her mother, locked herself in her room, and talked about wanting to die. She had friends at school who cut themselves with razors, and she was intrigued by what seemed to be an act of defiance. She tried it, too. “The pain felt so real and raw and mine,” she said.

Her parents took her to a family therapist, who, after several months, referred her to a psychiatrist. Laura was given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and prescribed Depakote, a mood stabilizer that, the previous year, had been approved for treating bipolar patients. She hid the pills in a jewelry box in her closet and then washed them down the sink.

She hoped that she might discover a more authentic version of herself at Harvard, where she arrived as a freshman in 2001. Her roommate, Bree Tse, said, “Laura just blew me away—she was this golden girl, so vibrant and attentive and in tune with people.” On her first day at Harvard, Laura wandered the campus and thought, This is everything I’ve been working for. I’m finally here.

She tried out new identities. Sometimes she fashioned herself as a “fun, down-to-earth girl” who drank until early morning with boys who considered her chill. Other times, she was a postmodern nihilist, deconstructing the arbitrariness of language. “I remember talking with her a lot about surfaces,” a classmate, Patrick Bensen, said. “That was a recurring theme: whether the surface of people can ever harmonize with what’s inside their minds.”

Watch “The Backstory”: Rachel Aviv on the challenges one woman faced while going off psychiatric drugs.

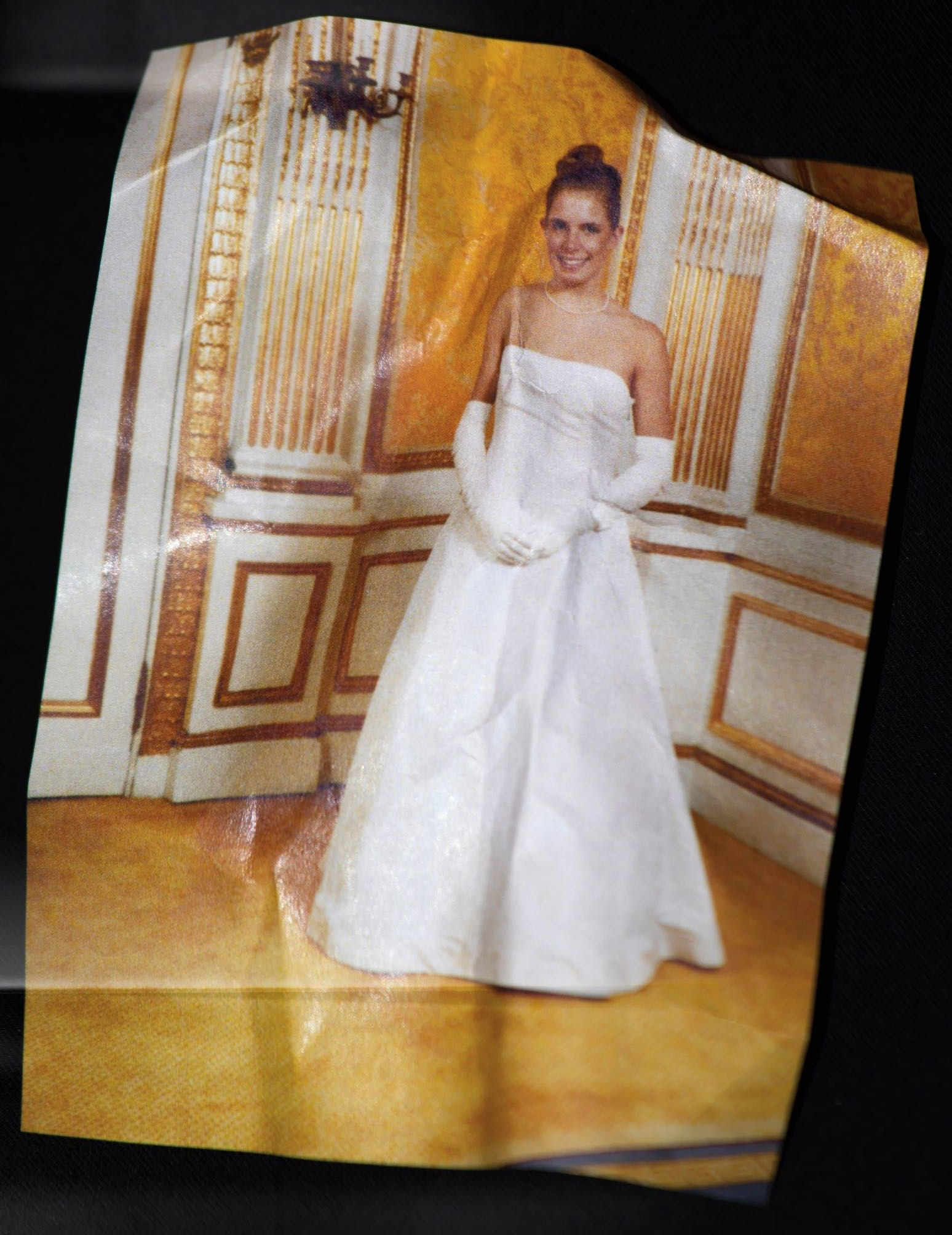

During her winter break, she spent a week in Manhattan preparing for two débutante balls, at the Waldorf-Astoria and at the Plaza Hotel. She went to a bridal store and chose a floor-length strapless white gown and white satin gloves that reached above her elbows. Her sister Nina said that, at the Waldorf ball, “I remember thinking Laura was so much a part of it.”

Yet, in pictures before the second ball, Laura is slightly hunched over, as if trying to minimize the breadth of her muscular shoulders. She wears a thin pearl necklace, and her blond hair is coiled in an ornate bun. Her smile is pinched and dutiful. That night, before walking onstage, Laura did cocaine and chugged champagne. By the end of the party, she was sobbing so hard that the escort she’d invited to the ball had to put her in a cab. In the morning, she told her family that she didn’t want to be alive. She took literally the symbolism of the parties, meant to mark her entry into adulthood. “I didn’t know who I was,” she said. “I was trapped in the life of a stranger.”

Before Laura returned to Harvard, her doctor in Greenwich referred her to a psychiatrist at McLean Hospital, in Belmont, Massachusetts. One of the oldest hospitals in New England, McLean has treated a succession of celebrity patients, including Anne Sexton, Robert Lowell, James Taylor, and Sylvia Plath, who described it as “the best mental hospital in the US.” Laura’s psychiatrist had Ivy League degrees, and she felt grateful to have his attention. In his notes, he described her as an “engaging, outgoing, and intelligent young woman,” who “grew up with high expectations for social conformity.” She told him, “I lie in my bed for hours at a time staring at the wall and wishing so much that I could be ‘normal.’ ”

The psychiatrist confirmed her early diagnosis, proposing that she had bipolar II, a less severe form of the disorder. Laura was relieved to hear the doctor say that her distress stemmed from an illness. “It was like being told, It’s not your fault. You are not lazy. You are not irresponsible.” After she left the appointment, she felt joyful. “The psychiatrist told me who I was in a way that felt more concrete than I’d ever conceptualized before,” she said. “It was as though he could read my mind, as though I didn’t need to explain anything to him, because he already knew what I was going to say. I had bipolar disorder. I’d had it all along.” She called her father, crying. “I have good news,” she said. “He’s figured out the problem.”

She began taking twenty milligrams of Prozac, an antidepressant; when she still didn’t feel better, her dose was increased to forty milligrams, and then to sixty. With each raised dose, she felt thankful to have been heard. “It was a way for me to mark to the world: this is how much pain I am in,” she said. Laura wasn’t sure whether Prozac actually lifted her mood—roughly a third of patients who take antidepressants do not respond to them—but her emotions felt less urgent and distracting, and her classwork improved. “I remember her carrying around this plastic pillbox with compartments for all the days of the week,” a friend from high school said. “It was part of this mysterious world of her psychiatric state.”

At parties, she flirted intently, but by the time she and a partner were together in bed, she said, “I’d kind of get hit with this realization that I was physically disconnected. And then I’d feel taken advantage of, and I would kind of flip out and start crying, and the guy would be, like, ‘What the heck is going on?’ ” Most antidepressants dampen sexuality—up to seventy per cent of people who take the medications report this response—but Laura was ashamed to talk about the problem with her psychiatrist. “I assumed he’d see sexuality as a luxury,” she said. “He’d be, like, ‘Really? You have this serious illness, and you’re worried about that?’ ”

During her junior year, her pharmacologist raised her Prozac prescription to eighty milligrams, the maximum recommended dose. The Prozac made her drowsy, so he prescribed two hundred milligrams of Provigil, a drug for narcolepsy that is often taken by soldiers and truck drivers to stay awake during overnight shifts. The Provigil gave her so much energy that, she said, “I was just a machine.” She was on the varsity squash team and played the best squash of her life. She was so alert that she felt as if she could “figure people out,” unpacking the details of their identities: she imagined that she could peer into their childhoods and see how their parents had raised them.

The Provigil made it hard for Laura to sleep, so her pharmacologist prescribed Ambien, which she took every night. In the course of a year, her doctors had created what’s known as “a prescription cascade”: the side effects of one medication are diagnosed as symptoms of another condition, leading to a succession of new prescriptions. Her energy levels rose and fell so quickly that she was told she had a version of bipolar disorder called “rapid cycling,” a term that describes people who have four or more manic episodes in a year, but is also applied, more loosely, to people who shift dramatically between moods. Sometimes Laura thought, Women who are happy and socialize like to buy dresses. She’d go to Nordstrom and buy two or three dresses. She recognized that this behavior was “textbook”—she had bought her own copy of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—but the awareness didn’t prevent the purchases.

Laura felt that the pressures of her junior year were paralyzing, so she did not return for the spring semester. That summer, she kept a journal in which she outlined her personal goals: “overanalysis must go”; “stop molding myself to the ideal person for my surroundings”; “find some faith in something, in anything.” But the idea of returning to Harvard that fall made her so distressed that she thought every day about dying. She took the semester off, and, at her request, her parents drove her to a hospital in Westchester County, New York. A psychiatrist there wrote that she “presents with inability to function academically.” At the hospital, where she stayed for two weeks, she was put on a new combination of pills: Lamictal, a mood stabilizer; Lexapro, an antidepressant; and Seroquel, an antipsychotic that she was told to use as a sleep aid. Her father, Lyman, said, “I had no conviction that the drugs were helping. Or that they weren’t helping.”

Read the entire article here: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/04/08/the-challenge-of-going-off-psychiatric-drugs

You can search CCHR’s Psychiatric Drugs Side Effects Database here: https://cchrint.org/psychdrugdangers/

SHARE YOUR STORY/COMMENT